Our guest post and book giveaway this week comes from Edward Zuckerman.

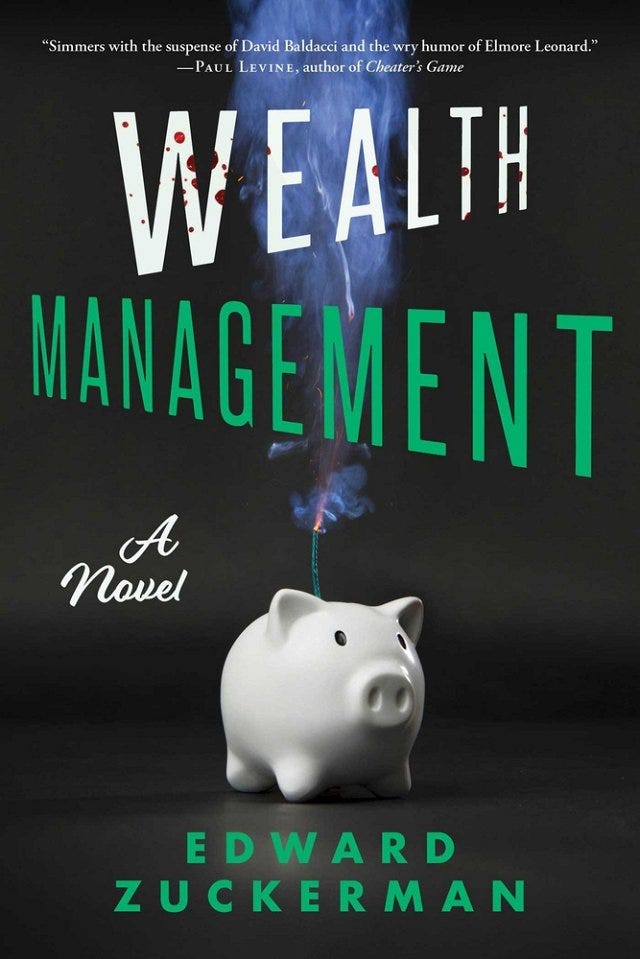

He's giving away a copy of his novel, Wealth Management, to a lucky winner.

To enter the giveaway, just request a copy from Ed through the contact page on his website. Enter by April 30, and he'll randomly select a winner from the entries.

Make sure to check out Ed's story about the "joys" of researching the Nigerian police!

*****

One of the characters in Wealth Management is a cop from Nigeria. To make it realistic, I wanted to meet and talk to some cops from Nigeria. Easier said than done!

How could I meet some African cops? I could go to Africa and get arrested, but that seemed less than ideal. I was writing a novel, a thriller called Wealth Management, and I wanted the characters to include a detective from Africa (he would travel to Switzerland to investigate a financial crime with a connection to Africa and terrorists.) To create the character, I could just make stuff up, or steal from novels set in Africa, or Google the night away. But I wanted my guy to sound and feel authentic and, as a former journalist, I know you can't beat reality. Yes, it is often "stranger than fiction." It is even more often simply more interesting.

So I wanted to meet and talk to African cops, preferably from a country where English was spoken. So I wrote a letter to the Gambian embassy explaining my request. No response. I knew a woman in California who was married to a Ghanaian, whose brother, she said, knew police officers in Accra. I sent a letter to her, to be given to her husband, to be forwarded to his brother, to be forwarded to said police officers.

No response.

Getting desperate, I logged onto Amazon and searched for "police in africa," and, lo and behold, found a book called Police in Africa. It included a chapter about the Nigerian Police Force written by an Oxford sociologist who had spent a year with them. I tracked down his address and sent him an email: "Hi, you don't know me, but I was wondering if you...etc." I did mention that I was a long-time writer for the TV show "Law & Order," which I thought might give me some cred.

It did, and he agreed to meet me, and I flew to England to see him (hey, tax-deductible business expense!), and we drank some beer and he told me about Nigeria and its police force and said he would arrange some introductions. Bingo. Now all I had to do was fly to Nigeria.

I set off with some trepidation. Lagos is, in a nutshell, a tough town. The population is fifteen million or thereabouts. Nobody knows for sure. The average daily temperature is about 90, with the humidity always over 80 percent. Every short walk I took around my hotel left me drenched with sweat, but at least it was safe, the Oxford sociologist said, as long as I walked during daylight hours. Lagos traffic jams ("go-slows") are legendary. The driver I hired to guide me around (for $35 a day) spent his nights sleeping in his car outside my hotel; the alternative was a six-hour roundtrip drive to his house across town. Taxis and Ubers are okay, the Oxford sociologist advised, except "don't get into a taxi with another person, that's how you get kidnapped."

As for the Nigerian police, they are notoriously corrupt, well known for shaking down motorists at checkpoints and worse. "If a policeman comes to your house and sees five thousand dollars on a table," one civilian told me, "you are dead. He will come back later and kill you." The criminals are world-class, too. One police officer I met, a man well-known for being honest, told me that when he drives cross country, he hides his uniform in the trunk of his car and removes his police license plates. If marauding armed robbers know he is police, they will know he has weapons and kill him to steal them.

And that's not all he told me. He and other good cops I spoke to gave me the kind of factoids that add texture to a story. When a police officer is killed, a sign is posted outside the station saying "Gone Too Soon" and giving his widow's bank account details. A police officer may read The New Dawn, the police department newspaper, in his station but will never carry it outside with him (see license plate anecdote above).

And there were bigger true stories:

One officer tracked and arrested a gang of Chadian killers near the Nigeria-Chad border. After they were jailed, a man showed up to offer the officer a massive bribe to make the case go away. (The man said the money came from the forlorn mother of one of the arrestees, who had sold her cows to raise the cash to free her "innocent" boy.) The officer declined, but his boss took the bribe, and the killers were freed, and they came after the officer for revenge and beat him so badly he lost an eye. Years later, he encountered his boss again at an official function and -- "He didn't look me in the eye."

Another officer investigated the case of a woman who flew home from London and was followed from the airport to her house by robbers who shot her and stole her purse. She was taken to a hospital, where she died. Her daughter called the officer and asked what had happened to the 30,000 pounds sterling she had wrapped in her girdle. (The robbers had not undressed her.) The officer suspected the doctor and nurses who had treated the woman at the hospital of both robbing and killing her. They confessed, he told me, after "persistent questioning, direct eye contact, and a persuasion toward empathy." The case was dropped, however, because the hospital's owner was well-connected. The good news: the officer's superiors knew he had solved the crime and for that he was rewarded.

Not all my interviews were that successful. Several officers suggested I speak to high-ranking officials at the FCIID (the Force Criminal Intelligence and Investigation Department), Nigeria's equivalent of the FBI. I found its headquarters on a ramshackle side street, looking like a derelict motel, with hand-painted signs pointing the way to various offices and warning lesser officials not to park in their superiors' spaces. Looming ironically over the mess was a half-completed high-rise intended to replace the current offices. It had been abandoned mid-construction following exposés of massive corruption. If the police couldn't get their own new headquarters erected honestly....

In a reception area, I gave the name of an official I had been told to see. The receptionist made a call and a middle-aged woman came and took me to her office. There, she told me she was an investigator and introduced me to the Principal Staff Officer to the Inspector General, who took me to the office of another senior officer, who took me to the office of a more senior officer, who may or not have been the Inspector General, or possibly the Assistant Inspector General; he wouldn't tell me. Instead he explained to me the meaning of the word "hierarchy," the rules of which I had violated. What I needed to do, he said, is get authorization from national police headquarters in Abuja and then he will tell me anything I want. And, by the way, don't let the door hit me in the ass on the way out. I told him good-bye and took a couple of pieces from a candy dish on a table by the door. By then I had what I needed anyway.

*****

Edward Zuckerman began his career as a journalist, writing about zombies, killer bees, talking apes and other subjects for Rolling Stone, Spy, the New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire, and many other magazines. He wrote two well-reviewed nonfiction books, The Day After World War III and Small Fortunes, and then moved into writing for television dramas, including the original “Law & Order” (50+ episodes), “Blue Bloods,” and “Law & Order: SVU.” He has won two Edgar Awards from the Mystery Writers of America and an Emmy for his work on “Law & Order.” He lives in Manhattan and Manhattan Beach, California. Wealth Management is his first novel.